April 5, 2012

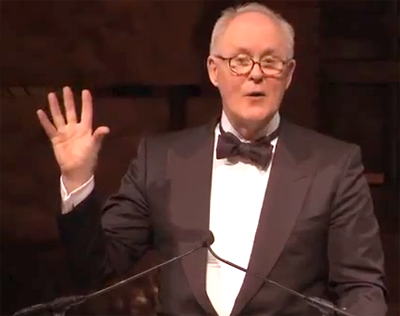

Lithgow on Joy in a Fretful World

In the course of a year, I represent the NASAA membership in many different gatherings, some to shape policy; some to gain knowledge; some to share ideas, provide information and build networks; and some to celebrate. I always have two purposes: to remind various audiences that state arts agencies are an essential infrastructure in the cultural life of the United States and merit their support, and to gather resources I can make available to members.

One of the most inspiring series of events each year is the gala sponsored by the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities (PCAH) to celebrate the awardees of the National Medal of Arts and the National Medal of Humanities. The keynote speaker this year was actor and author John Lithgow. His presentation, “Joy in a Fretful World,” was so uplifting that I want to share it with you, and I thank our excellent colleagues at PCAH for their permission to do so. I hope the excerpt below will encourage you to read the entire speech and consult the full list of award winners. The excerpt begins after Lithgow explains that he was one of only a few artists appointed to a congressional commission of 50 prominent people charged with generating 10 “succinct initiatives to promote the cause of the humanities . . . with persuasive arguments for putting them into practice.”

At first, I sat silently among them, listening to their polished phrases and their penetrating insights. In their midst, I felt like a sullen schoolboy in the slow learners’ group. Finally, in a morning break-out meeting of 10 Commission members, I summoned up the courage to speak. My bottled-up thoughts tumbled out in a kind of passionate blurt. I’m an actor. Histrionics are my stock in trade. So I was predictably histrionic: “The humanities are indispensable to a rounded human being!” I cried. “We should declare that fact loud and clear! Democracy can only function with an educated citizenry, grounded in the humanities! People have forgotten that the humanities are bound up with their own lives! We have to remind them of that! The job has fallen to us! The humanities in education are the wellspring of empathy! Cooperation! Civil discourse! Collaboration in a polarized world! They create a habit of learning that lasts a lifetime! They are a source of self-knowledge! Life without them is drab and joyless! Joy! That’s the word! Joy! The arts and the humanities instill JOY!”

Or words to that effect.

To my mortification, that afternoon this impassioned peroration was quoted, verbatim and at length, to the full Commission. In response, one of the more cool-headed and hard-nosed Commission members dryly pointed out that an American worker without a job might be singularly unimpressed with my belief in the “joy” of humanistic pursuits. Another member, a state governor and a seasoned veteran of governmental policy wars, suggested that, in any argument before Congress in favor of expanded federal programs in the humanities, the word “joy” is probably best left out. As if chastened by a pair of stern schoolmasters, I deferred to their better judgment. But I was unrepentant. In fact, I was secretly pleased that I had livened up the proceedings and unembarrassed by my newly minted status as the Commission’s comic relief.

Because in fact, I steadfastly believe everything I said that day. I believe that civil discourse, self-knowledge, empathy, the habit of learning and, yes, the capacity for joy are indeed learned skills and that they can be most effectively taught to young people through the arts and humanities. And I believe most fervently that the health of a democracy absolutely depends on these qualities in the grown-up electorate.

A lot of this conviction comes from my own educational background. In a peripatetic childhood I went to eight different small town public schools—in Ohio, Massachusetts and New Jersey. Surprisingly enough, those far-flung schools provided me with a marvelous, broadly based secondary education, one that sent me on a clear trajectory to a first-rate college by the time I was 17. This was an earlier era, of course, when public schooling was not nearly as embattled and cash-strapped as it is today; when most high schools offered classes in art, music and multiple foreign languages; when testing was not yet paramount in everyone’s mind; when school standards were not yet the subject of pitched political battles; and when no one had yet coined that cold, forbidding and ubiquitous acronym for science, technology, engineering, and math: STEM!

Ah, yes, STEM! The very word gives me the screaming whim whams. I am a humanist, you see. I left behind science, technology, engineering, and math many years ago. I was never much good at all that stuff to begin with, and whatever I did learn I’ve long since forgotten. Nowadays it’s all I can do to calculate a tip. Don’t get me wrong. I fully appreciate the vital importance of STEM in every child’s education. For our economy to grow, for our nation to stay competitive, and for our young people to get good work in a daunting job market, our educational system must excel in each of the STEM subject areas. But to my mind, the arts and humanities are every bit as important as STEM. And a balance must be struck.

The very word STEM provides me with an apt poetic metaphor to drive home my point. Let me offer it to you, with abject apologies to our poet-medalists John Ashbery and Rita Dove. Picture a flower—a big bright flower in full bloom. The flower’s stem is, well, STEM! Science, technology, engineering, and math. It is the superstructure, the infrastructure, the support system of the flower itself. And the arts and humanities? Why, they’re the blossom of course—the source of the flower’s beauty, fragrance, and identity, the visible mark of its health, and the wherewithal for the flower to reproduce itself. The stem is functional, strong, and essential. But pare away the blossom and the stem has no purpose, no function, no value. In time it will wither and die. It cannot survive the loss. So much for STEM.

I know, I know. I’ve taken this way too far. I have not only strained a metaphor, I have practically strangled it to death. But here’s the point (and I just bet that it stays with you). The blossom is what we love about a flower. It’s what inspires us. It’s what engages our senses and our emotions. It is the reason we plant the flower in the first place. And yes, like the arts and the humanities, it’s what gives us joy.

Joy. We’re back to that word. By now it has practically become the theme of my speech: joy in a fretful world. We are living through perilous times. The last few years have seen our country’s most destructive terror attack, the fog of war, the gravest economic conditions since the Depression, natural disasters of incomprehensible magnitude accompanied by the ominous drumbeat of climate change. These events and conditions beget fear. Fear deadens our spirit and darkens our national mood. It begets denial, mutual suspicion, and divisiveness. Fear polarizes us and paralyzes us. You see evidence of it everywhere you look—in every newspaper, newscast, blog and, most blatantly, in every political campaign ad on TV.

You see it everywhere but not here. Not here and not tonight. And why not? Well, just look at who we are honoring this evening and what we are honoring them for. The arts and humanities are our bulwark against fear. Tonight’s honorees don’t avoid harsh truths—they engage them. They don’t divide us from each other, they connect us and reveal to us our common ground. Their gifts to us are a mixed bag, to be sure, but what a glorious mixed bag it is. And what gifts. Think of Andre Watts plumbing the depths of Schumann and Chopin. Think of Rita Dove, poet laureate and passionate ballroom dancer. Think of Mel Tillis crooning “Coca Cola Cowboy” at the Grand Old Opry. Think of Anthony Appiah confronting and dissecting the politics of race, Charles Rosen breathing new life into the music of Franz Liszt, Will Barnet defying age by creating beautiful images late into his 90s, Amartya Sen wielding economics—economics! the dismal science!—as a weapon in the global war on poverty and famine. And think of film star Al Pacino returning yet again to Broadway last year in The Merchant of Venice, and performing the best Shylock that I, for one, have ever seen. What do these vastly different Americans and all their cohonorees have in common? They are men and women who give us hope, who broaden our thinking, who enlarge our hearts, who stimulate and delight us, who heighten our sense of ourselves and illuminate us about the lives of others, who challenge us, who educate us, and who give us the rare gift of joy. Think of all of them, the recipients of the 2011 National Medals of Arts and of Humanities, and rejoice.

Thank you.

In this Issue

State to State

- Indiana: Grant Panel Audio Files Service

- Massachusetts, Florida: Blogging to Broaden Reach

- Utah: Connecting Constituents with Video Poems

- Arizona, California, D.C.: Using Facebook to Reap Public Benefits

Legislative Update

Executive Director's Column

Research on Demand

SubscribeSubscribe

×

To receive information regarding updates to our newslettter. Please fill out the form below.